Goodhart’s Law: When a Target Leads Us Astray

One of the more oft-cited business and productivity slogans is, "you can't manage what you don't measure." Yet, how often are we chasing the wrong metric and exacerbating the problem we are trying to solve? When it comes to working with complex natural systems like agriculture, the answer is more often than not.

One of the best articulations of this phenomenon is Goodhart's law.

In its simplest form, Goodhart's law states, "when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure."

This idea has been widely discussed in business, data analytics, and other metric-heavy disciplines. The law is named after its creator Charles Goodhart, a British economist.

The classic story often used to describe Goodhart's law takes place in India during British rule. The colonial government was concerned with the number of venomous snakes, so they had the idea to enlist the populace to help eradicate the snakes. The government offered a bounty for every dead cobra brought to its gates.

At first, this was a huge success. Dead cobras piled up outside the gates, and the government felt proud of their clever strategy. Soon after, it was discovered that some enterprising people were breeding cobras with the intention of killing them later for extra income. As soon as the government discovered this, they abruptly discontinued the program. The cobra breeders no longer had any use for the newly bred snakes and released them into the wild, causing a rise in the cobra population.

Ultimately the problem was no better than when it began.

A similar myopic misstep happened in agriculture after the invention of the Haber-Bosch method, which produced abundant and cheap synthetic nitrogen fertilizer. This came at a time when food scarcity and famine were a real possibility in many countries. The target was thus set to produce vast quantities of food using these new synthetic fertilizers. The movement towards industrialization was further intensified by the launch of the Green Revolution and the hybrid grain varieties bred to be compatible with synthetic fertilizers and produce higher yields.

As food produced under this model came to dominate supermarkets and dinner tables, there has been a concomitant rise in obesity, type two diabetes, and other chronic diseases linked to our industrialized food supply.

We already produce enough food to feed 10 billion people, and for the first time in history, more people die from overeating than not having enough to eat. Much of the world's food supply has a drastically reduced nutritional profile, contributing to a growing number of overfed and undernourished populaces.

A recent study from UT Austin's Biochemical Institute shows that many common fruit and vegetable varieties have significantly less nutritional value than those grown before the widescale adoption of industrial agriculture. Essential nutrients like protein, calcium, phosphorus, iron, ascorbic acid, and riboflavin have declined from 6 percent to 38 percent. This doesn't account for several other vital nutrients that weren't studied in the 1950s but have certainly dropped off.

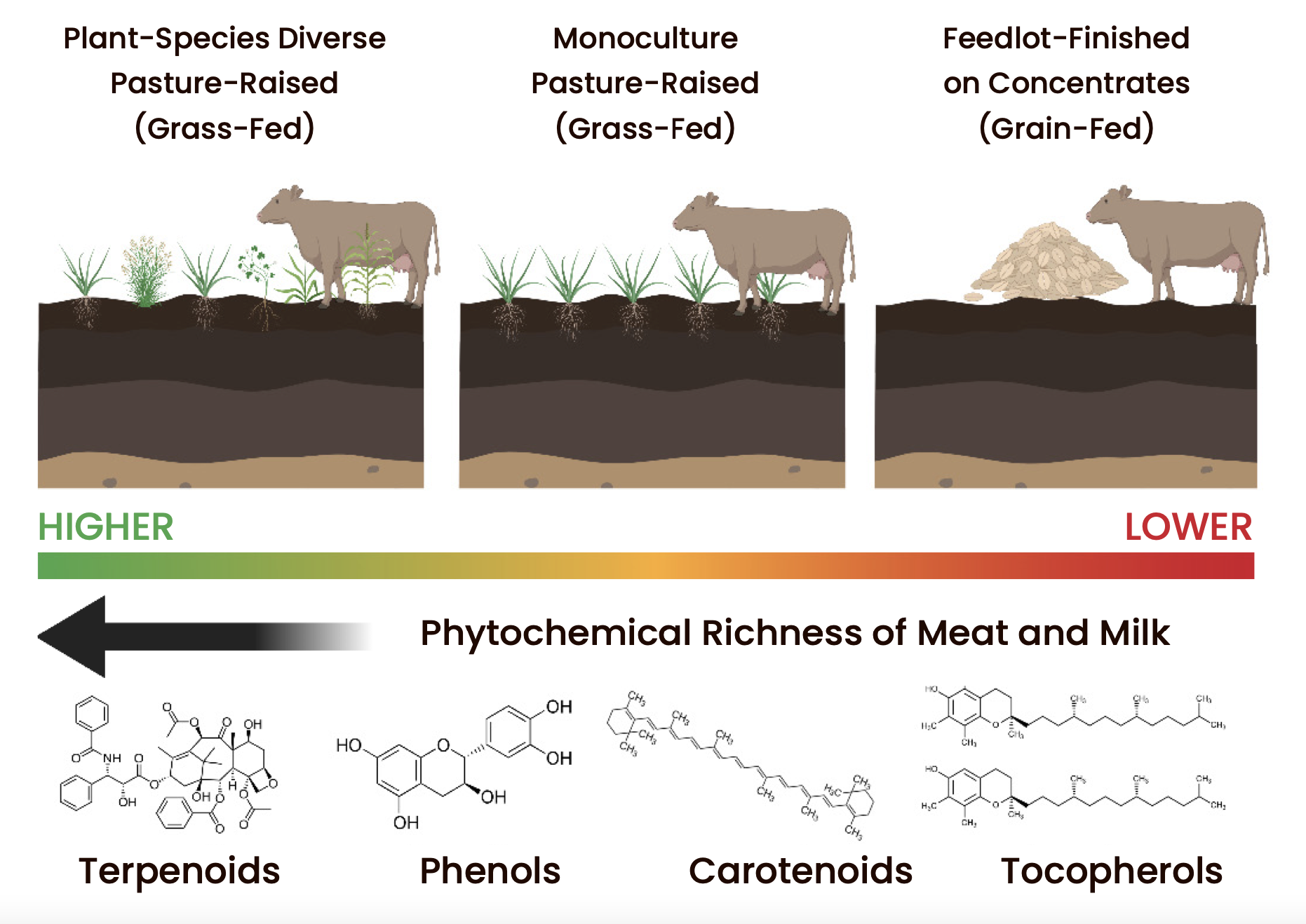

Conversely, there is increasing evidence of higher nutritional integrity in crops and livestock grown in regenerative systems than in their conventionally grown counterparts. One study shows improved soil health resulting from integrated farming practices is the linchpin for nutrient-dense food production.

Image Credit: Bio Nutrient Food Association

So what is the antidote to Goodhart's law and this example of our agriculture system's misguided and antiquated approach to growing food for quantity with no regard for quality?

We need a better measure of success for our agriculture system. Agriculture can positively impact people and ecology more than any other endeavor or industry. Therefore, it's imperative that we design our agriculture systems so that our target and guiding metrics produce the maximum amount of benefits system-wide.

Growing food to produce the highest quality crop with complete nutritional integrity is a better target for our agriculture systems. With this as our target, we can transform our food system from an oversupply of empty calories to an abundance of nutrient-dense food that heals and nourishes. In addition, this solves many of the downstream problems created by industrial agriculture as better stewardship of our soil, water, landscapes, and people are central to producing nutrient-dense food.

As we continue to unravel the second and third-order effects of industrial agriculture, it will become clearer that there is a pressing need for a better way forward. The concept of Goodhart's law can act as a guide as a new agriculture system takes hold. The best measure will have a cascade of positive downstream effects, spreading healthy and vitality throughout the system.

Cover image credit: Ribbonfarm